The Checklist Manifesto (book)

✒️ Note-Making

🔗Connect

🔼Topic:: Productivity (MOC) 🔼Topic:: Memory, Attention and cognitive load (MOC)

💡Clarify

🔈 Summary of main ideas

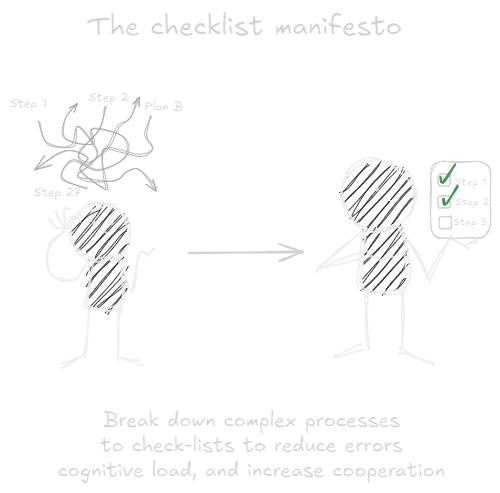

- Knowledge overload - Nowadays, our problem is not a lack of knowledge, it is widely available and in abondance. We fail due to inaptitude, not ignorance. We have difficulties in finding ways to remember and implement all that we know

- Checklists reduce errors - by thinking about the action in advance, we can increase of chances of avoiding errors by noting explicitly the main risks of error and make sure that we address them. For example, having a checkbox of "make sure to put gloves" before a surgery to reduce risks of infection.

- Checklists improve cooperation - similar to the complexity at the individual level, working with others add more degrees of complexity. Using a checklist as a method to "bind" people to a process while allowing them freedom of expression is a good way to verify that cooperation is achieved.

🗒️Relate

⛓ by following this method, what will happen? What is the goal of this book? You will be better equipped with managing complex actions through the use of check lists

🔍Critique

✅ relevant research, metaphors or examples that helps to convey the argument

❌ the logical jumps, holes or simply cases where it is wrong...

🧱 Implementations and limitations of it are...

🗨️Review

💭 my opinions on the book, the writers style... This book is nice, and almost as short as it needs to be. Some examples are overly described, maybe even at ADHD level, and sometimes he's not really talking about checklists rather than simply mechanisms of cooperation. Could have been an article, but the content is interesting.

🖼️Outline

Introduction

In a world with increasing Complexity, it's more likely that:

- You wont be able to perform tasks by yourself

- Higher complexity leads to more serious errors

We no longer live in a world where the main problem is ignorance. All the necessary knowledge is "out there". The problem therefore is to make good use of that knowledge. Following the right principles is difficult even if we remember them.

- we have just two reasons that we may nonetheless fail. The first is ignorance—we may err because science has given us only a partial understanding of the world and how it works.

- The second type of failure the philosophers call ineptitude—because in these instances the knowledge exists, yet we fail to apply it correctly.

- now the problem we face is ineptitude, or maybe it’s “eptitude”—making sure we apply the knowledge we have consistently and correctly.

- Getting the steps right is proving brutally hard, even if you know them.

- It is the complexity that science has dropped upon us and the enormous strains we are encountering in making good on its promise.

- It is not clear how we could produce substantially more expertise than we already have. Yet our failures remain frequent. They persist despite remarkable individual ability.

- the volume and complexity of what we know has exceeded our individual ability to deliver its benefits correctly, safely, or reliably. Knowledge has both saved us and burdened us.

Why Do We Need a List

As individuals, our greatest problem is no longer the lack of knowledge, we have the whole internet at our fingertips, the problem is implementing knowledge in an efficient and error free way. The recommended way to do this is by delegation. To store to a later time some of your mental effort now (creating the list) to save effort on a future time when you will need it (in times of pressure or uncertainty) Effort Storing.

- The knowledge exists. But however supremely specialized and trained we may have become, steps are still missed. Mistakes are still made.

What is a List

A list is a minimal collection of the necessary steps to succeed in the mission. Systematical Thinking The list should be flexible and changeable by the working parties as the process and task develop. The list will usually contain the steps that don't demand too much focus or mental effort, which are part of the "management" of the task (the things you have to verify).

Once we have a list, we can be more focused and relax because we know we are safe from errors if we only Trust the Process

We can define three sets of problems Problems:

- Simple - usually comes with basic instructions, that after several times you have enough experience to do them easily and automatically, like baking a cake.

- Hard - like flying a missile to space, it requires a lot of knowledge, cooperation and timing from many people, but usually once you crack the task, its easier to implement the next time.

- Complicated - similar to hard, but succeeding once doesn't make it (completely) easier the next time, like raising a child. Surely there are some best practices, but you can't replicate the process and get the same result.

- Faulty memory and distraction are a particular danger in what engineers call all-or-none processes: whether running to the store to buy ingredients for a cake, preparing an airplane for takeoff, or evaluating a sick person in the hospital, if you miss just one key thing, you might as well not have made the effort at all.

- Checklists seem to provide protection against such failures. They remind us of the minimum necessary steps and make them explicit. They not only offer the possibility of verification but also instill a kind of discipline of higher performance.

- checklists seem able to defend anyone, even the experienced, against failure in many more tasks than we realized. They provide a kind of cognitive net. They catch mental flaws inherent in all of us—flaws of memory and attention and thoroughness.

- What results is remarkable: a succession of day-by-day checks that guide how the building is constructed and ensure that the knowledge of hundreds, perhaps thousands, is put to use in the right place at the right time in the right way.

- of the experts to manage the complexities. They in turn know better than to rely on their individual abilities to get everything right. They trust instead in one set of checklists to make sure that simple steps are not missed or skipped and in another set to make sure that everyone talks through and resolves all the hard and unexpected problems.

The Idea

The list not only helps us remember the small forgettable tasks, and clears our mental capabilities to the more complex issues, it also helps us to coordinate Cooperation, organize, and turn cooperation into a habit between groups. This way, the check-list not only solves simple problems, but also lays the foundation for solutions for complex problems. Coordination should be both recurring ("before each x stage we meet"), and both in ad-hok cases ("if y happens we stop and meet"). Cooperation between different units enables the usage of various fields of knowledge, otherwise inaccessible to us since we can't be super-experts in everything, and having all the necessary knowledge for complex problems ourselves. The goal of the meetings is to discuss problems that might occur, coordinate expectations, and promote healthy communication.

- The philosophy is that you push the power of decision making out to the periphery and away from the center. You give people the room to adapt, based on their experience and expertise. All you ask is that they talk to one another and take responsibility. That is what works.

- the real lesson is that under conditions of true complexity—where the knowledge required exceeds that of any individual and unpredictability reigns—efforts to dictate every step from the center will fail. People need room to act and adapt. Yet they cannot succeed as isolated individuals, either—that is anarchy. Instead, they require a seemingly contradictory mix of freedom and expectation—expectation to coordinate, for example, and also to measure progress toward common goals.

- complexity a routine. That routine requires balancing a number of virtues: freedom and discipline, craft and protocol, specialized ability and group collaboration. And for checklists to help achieve that balance, they have to take two almost opposing forms. They supply a set of checks to ensure the stupid but critical stuff is not overlooked, and they supply another set of checks to ensure people talk and coordinate and accept responsibility while nonetheless being left the power to manage the nuances and unpredictabilities the best they know how.

- the more familiar and widely dangerous issue is a kind of silent disengagement, the consequence of specialized technicians sticking narrowly to their domains. “That’s not my problem” is possibly the worst thing people can think,

- Giving people a chance to say something at the start seemed to activate their sense of participation and responsibility and their willingness to speak up.

How to Create an effective Check-list

We can distinguish between two types of list:

- Read-Do: This checklist demands that we follow it step by step, first making sure we understand the next step, preform it, and mark it as done. This is more relevant in linear processes that have a high risk if steps are not done in the correct order

- Do-Confirm: This checklist only requires that once the process is done, we mark all the completed steps and make sure that no step was missed. This is more relevant in asynchronous/simultaneous processes where it is not critical that each step will be done in order, but only to make sure it was not missed.

The trade-off between Read-Do and Do-confirm is speed vs safety. Read-Do is more rigid, and verifies we complete all the necessary steps, but it creates points of friction because you have to stop at each step. While the Do-confirm is opposite, you act as you normally do, but you might still make mistakes because you preformed a step incorrectly, or missed it and now it is too late.

The list short be short, updatable, and user-facing based on the type of the user. No need to include the things that happen naturally.

- Bad checklists are vague and imprecise. They are too long; they are hard to use; they are impractical. They are made by desk jockeys with no awareness of the situations in which they are to be deployed. They treat the people using the tools as dumb and try to spell out every single step. They turn people’s brains off rather than turn them on. Good checklists, on the other hand, are precise. They are efficient, to the point, and easy to use even in the most difficult situations. They do not try to spell out everything—a checklist cannot fly a plane. Instead, they provide reminders of only the most critical and important steps—the ones that even the highly skilled professionals using them could miss. Good checklists are, above all, practical.

- By themselves, however, checklists cannot make anyone follow them.

- You must define a clear pause point at which the checklist is supposed to be used

- You must decide whether you want a DO-CONFIRM checklist or a READ-DO checklist. With a DO-CONFIRM checklist, he said, team members perform their jobs from memory and experience, often separately. But then they stop. They pause to run the checklist and confirm that everything that was supposed to be done was done. With a READ-DO checklist, on the other hand, people carry out the tasks as they check them off—it’s more like a recipe.

- The checklist cannot be lengthy. A rule of thumb some use is to keep it to between five and nine items, which is the limit of working memory.

- The wording should be simple and exact,

- a checklist has to be tested in the real world,

- It is common to misconceive how checklists function in complex lines of work. They are not comprehensive how-to guides, whether for building a skyscraper or getting a plane out of trouble. They are quick and simple tools aimed to buttress the skills of expert professionals.

- The reason is more often that the necessary knowledge has not been translated into a simple, usable, and systematic form.

Setbacks in Embracing Checklists

sometimes it might feel embarrassment to use a checklist, as if it is an indication of our lack of expertise Mastery. We should view it however as a sign of it. As makers of checklists, we use our expertise to our fullest by embedding it into a process. Feynman Technique

We have no other choice rather than to use systems for our benefit, because if we don't we will simply fail, which is much worse than any damage to our ego. Image vs core

Don't view checklists as another box to be ticked, this is only a symptom of a larger principle, which is creating systems that will facilitate productive work, with fewer errors and higher cooperation.

- Just ticking boxes is not the ultimate goal here. Embracing a culture of teamwork and discipline is.

- It somehow feels beneath us to use a checklist, an embarrassment. It runs counter to deeply held beliefs about how the truly great among us—those we aspire to be—handle situations of high stakes and complexity.

- The fear people have about the idea of adherence to protocol is rigidity. They imagine mindless automatons, heads down in a checklist, incapable of looking out their windshield and coping with the real world in front of them. But what you find, when a checklist is well made, is exactly the opposite. The checklist gets the dumb stuff out of the way, the routines your brain shouldn’t have to occupy itself with

- One essential characteristic of modern life is that we all depend on systems—on assemblages of people or technologies or both—and among our most profound difficulties is making them work.

- When we look closely, we recognize the same balls being dropped over and over, even by those of great ability and determination. We know the patterns. We see the costs. It’s time to try something else. Try a checklist.