Ethics of Ambiguity (book)

🔗Connect

🔼Topic:: Existentialism (Map) 🔼Topic:: Simone de Beauvoir

✒️ Note-Making

💡Clarify

🔈 Summary of main ideas

🗒️Relate

⛓ Life lessons, action items

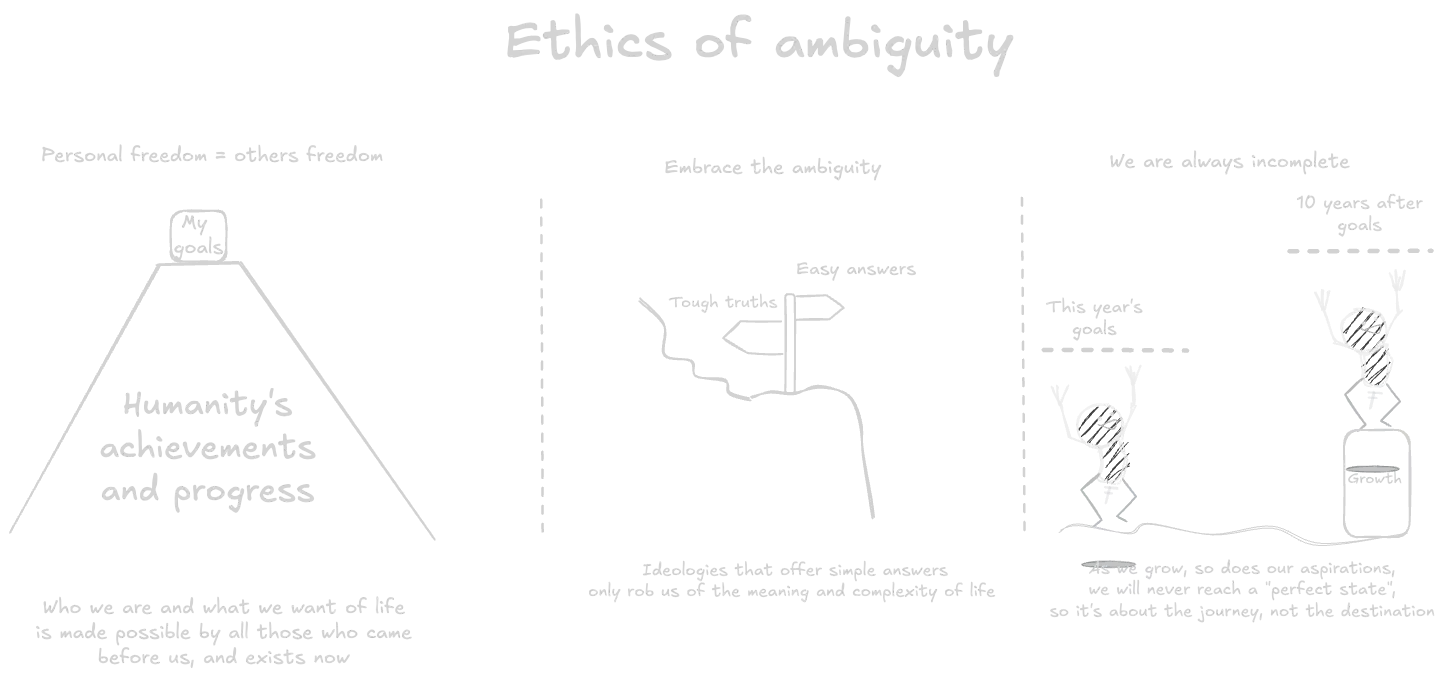

- With great freedom, comes great responsibility - we are the makers and actors of our own morality. We are born free, but it is only with conscious action that we can "will ourselves free" and convert potential freedom into meaning, morality and goals.

- Embrace the failure (ambiguity) - don't be limited by it, and don't ignore it. Realize that to fail is a natural part of transcendence. A person who never fails is one who never tries.

- Freedom of others - we are deeply connected and shaped by others and our social environment. Therefore to be true to the will to life and to will ourselves free, we must continue this by pursuing the freedom of others as well.

- To be free is to be incomplete - it's to decide that we are not yet done in this world, we are neither god nor rock. We will always have a mission, we will always lack something in our being, and we will never stop perusing it, changing, growing, failing, and transcending along the way.

🔍Critique

✅ by following this method, what will happen?

- Responsibility - we will understand our duty to create meaning in our lives and pursue freedom.

- connection - we will have a stronger sense of comradery with our fellow men since we realize that our freedom is tied to theirs.

- ambiguity is a feature, not a bug - between being an object and a subject, we realize that this is where we can fulfill ourselves, to always try, always fail.

❌ the logical jumps, holes or simply cases where it is wrong...

- why do I owe others - I do agree and adore the point of how our freedom is connect to others, so we should aspire to increase others' freedom as well. However, this point is pretty weak in her argument, and no other justification given other than "freedom is infinite, and humanity is infinite, therefore...". That is the drawback of an existentialist believe that isn't tied directly to values or virtues.

🧱 Implementations and limitations of it are...

- as with all existential theories, no answers are given, rather only methods. Meaning is not given on a silver platter, and no known rules to follow. But this is exactly the point, we have to make our own rules, it's our responsibility.

- The "types of humans" sometimes described as hierarchical (you start from x, then evolving into y), and sometimes as parallels (some people are x, others are y). However, the main component is missing - how do these people can evolve and become the free man?

🗨️Review

💭 my opinions on the book, the writers style...

- Wow, wow wow. This was simply amazing. In such few pages Simon can be so accurate in her description of human existence and how one should approach it. It will carry on with me.

- The last third of the book is rather affected by the political situation of the time, making it a big less relevant to today, but still there are ideas to take from there.

- There is not a lot of structure to the book, and not a lot of explanations of concepts that she believe are well known and essential to her work. Sometimes only after 10-20 pages the explanation arrives and suddenly it becomes clear. Also, reading a summary before/during reading this book was extremely helpful.

🖼️Outline

📒 Notes

Part 1 - Ambiguity and Freedom

People are torn between two aspects, being a subject and an object. On the one hand, we strongly feel our sense of subjectivity, our desire to be, to fulfill our goals, to be everything for ourselves, of agents with a will. And yet, we are objects, creatures that are destined to die, tools to be used, to be viewed by and view others as objects.

This Ambiguity, between what we are perceived and what we aspire to be, shouldn't be avoided, as some philosophers claim, but rather embraced. Challenge. No ethical theory can or should point us to one end of the other, to simplify our complex life. Simplicity. Complexity. This ambiguity can be stressful and scary, which pushes us towards bad faith. lost in the infinite

The difference between ambiguity and absurdity is that absurdity claims that life is meaningless, while ambiguity means that meaning can be forged, and reshaped during our lifetime. Absurdity of existence

Existentialism recognizes that this resolution into one or the other side of the binary dilemma is impossible; no matter how much people try to impose their will on the world and pursue their goals, they will inevitably fail. This Failure is precisely why people need ethics: to give themselves something to strive for.

Since if you were pure subjectivity, an all powerful god, you won't need ethics since the world will be as you wish. And if you were pure object, you still won't need ethics since you don't have a will of your own. By denying meaning, or fully embracing an external one, your actions are not your own, you are a pawn in someone else's game, therefore ethics are irrelevant to you. morality requires free will. Therefore, morality is subjective but meaningful precisely because all meaning is subjective. Relativism

Don't deny your will for transcendence, but don't be lost in it either. Embrace the failure of truly fulfilling oneself. Agency transcendence

By embracing their ambiguity rather than despairing in it, people can come to desire not the impossible moral perfection promised to them by other, abstract systems of ethics, but rather desire to identify as a of being. All action are deeply connected to our being, because action results from people’s abilities, values, and commitments. The only fulfillable desire is the desire to authentically become oneself, which is the same as the desire for one’s own freedom—one’s capacity to be what one is, rather than trying to become a value set out by someone else.

Existence and freedom, is both describing a lack in our being, and attempting to fill it at the same time. Since if we are not lacking, if we are complete and perfect, then we are either gods or objects. Forever unchanging, desire noting. To be, to become, is therefore deciding that we are not yet complete, that we still have a mission, a room to grow, and pursue to fulfill those aspirations simultaneously. This will is never ending To be is to be incomplete.

Freedom, is both the starting point and ultimate goal of ethics: everyone is naturally free, meaning they are capable of spontaneously acting, but it is up to them to turn this natural freedom into genuine moral freedom by “willing themselves free.” this is not an easy task, laziness, cowardice, impatience are some factors that might make us choose to not be free, to not actualize our freedom.

Meaning that freedom is both a blessing and a curse, we are free to do as we please, but we also have to construct the rules we are acting and being valued upon. We are both the actor and the judge. We bear the Responsibility of creating our own meaning. To wish to be free, and to be moral, are therefore one and the same. Meaning is Crafted

If that is the case, it appears as if everything is subjective, even sophistic. Meaning we are "alone in the universe" without a common language since morality is subjective.

Marx and Kant both try to solve the unity between subjectivity and freedom in a different way. Immanuel Kant says: "you must, therefore you can". Meaning that by transcending our personal self and understanding the pure logical rules that govern us, only then we are truly free to act. Karl Marx says: "you must, therefore you can't". Meaning that we humans are restricted both in actual physical terms, but also in terms of cultural perceptions based on the class we are born into. It affects, distorts and limits our point of view, in a way that disrupts our freedom as well. Only by revolting and releasing ourselves from the class struggle, could we be truly free.

To be truly free requires carefully reflecting on one’s individual actions and broad personal project, since freedom lies in the ambiguity between subjectivity and objectivity, which means establishing continuity between one’s past, present, and future. For example, even if we set ourselves goals, instead of spontaneous acting, we still haven't escaped our basic freedom and achieved true freedom, depending on the relationship between ourselves and our goals. If our goals are merely tools, stepping stones on our way to transcendence, then it is okay Trust the Process. A creator who has goals which will turn him into a better person, a better creator, which will help him bring more meaning and value into the world, then this is freedom. On the other hand, if "your goal is your life", and you wish it simply for achieving it, then you became the object, the slave to your goal, and you are no longer free. For example, goals to be more successful at work/money are usually those types of goals. Life's Mission

Freedom also requires Honesty. On the one hand, trying to do the impossible is a limited use of our freedom, since it denies our objectivity, who we are and our capabilities. We are then lost in a dream, forgetting ourselves. On the other hand, to give up every time we fail is hardly being free, since we let external situations dictate who we are. We need both Grit and Self-awareness.

Our actions must be constantly examined. To see that we are truly aiming at freedom and acting in a free way. That's the difference between the serious man and a free man, that we continuously question our goals and actions. That is very similar to the scientific method, by creating hypothesis and testing them in reality, vs simply make assumptions and never validating them. scientific method

Therefore, the will to freedom is a never ending struggle between failures and transcendence. To deny failures, or to be limited by them is to deny freedom. However, this endless struggle will end eventually when we die. The only solution for continuity in this Will to life is to pursue the freedom of others, to realize freedom as an indefinite unity. This idea is similar to economic growth 2bc, in order for me to prosper, I need those around me to prosper as well Happiness is shared, otherwise they won't be able to buy my products, the infostructure will be horrible, or they won't innovate at all. Either way, the world today is a positive sum situation, and it's the same in economy as it is in existentialism. win win situations.

On evil - While she agrees that people cannot will themselves unfree, she notes that people start with natural but not moral freedom and can certainly prevent themselves from reaching moral freedom by refusing to accept life’s ambiguity or work for the betterment of oneself and the world. This is the equivalent of moral evil for existentialists. Importantly, de Beauvoir notes, whereas many ethical systems chalk evil up to human imperfections or moral error, only existentialists hold people truly and completely responsible for their errors, which is why the existentialist picture of ethics actually provides a more complete account of good and evil and is less forgiving of selfishness and indifference to others.

- between the past which no longer is and the future which is not yet, this moment when he exists is nothing. This privilege, which he alone possesses, of being a sovereign and unique subject amidst a universe of objects, is what he shares with all his fellow-men. In turn an object for others, he is nothing more than an individual in the collectivity on which he depends. (Location 32)

- at every opportunity, the truth comes to light, the truth of life and death, of my solitude and my bond with the world, of my freedom and my servitude, of the insignificance and the sovereign importance of each man and all men. (Location 55)

- Since we do not succeed in fleeing it, let us therefore try to look the truth in the face. Let us try to assume our fundamental ambiguity. It is in the knowledge of the genuine conditions of our life that we must draw our strength to live and our reason for acting. (Location 57)

- man, in his vain attempt to be God, makes himself exist as man, and if he is satisfied with this existence, he coincides exactly with himself. It is not granted him to exist without tending toward this being which he will never be. But it is possible for him to want this tension even with the failure which it involves. (Location 96)

- To attain his truth, man must not attempt to dispel the ambiguity of his being but, on the contrary, accept the task of realizing it. (Location 105)

- To exist genuinely is not to deny this spontaneous movement of my transcendence, but only to refuse to lose myself in it. (Location 108)

- It is human existence which makes values spring up in the world on the basis of which it will be able to judge the enterprise in which it will be engaged. (Location 120)

- because man is abandoned on the earth, because his acts are definitive, absolute engagements. He bears the responsibility for a world which is not the work of a strange power, but of himself, where his defeats are inscribed, and his victories as well. (Location 132)

- One can not start by saying that our earthly destiny has or has not importance, for it depends upon us to give it importance. (Location 135)

- An ethics of ambiguity will be one which will refuse to deny a priori that separate existants can, at the same time, be bound to each other, that their individual freedoms can forge laws valid for all. (Location 159)

- In the eyes of the Marxist, as of the Christian, it seems that to act freely is to give up justifying one’s acts. This is a curious reversal of the Kantian “you must; therefore, you can.” Kant postulates freedom in the name of morality. The Marxist, on the contrary, declares, “You must; therefore, you can not.” (Location 204)

- Freedom is the source from which all significations and all values spring. It is the original condition of all justification of existence. The man who seeks to justify his life must want freedom itself absolutely and above everything else. (Location 226)

- To will oneself moral and to will oneself free are one and the same decision. (Location 231)

- To will oneself free is to effect the transition from nature to morality by establishing a genuine freedom on the original upsurge of our existence. (Location 239)

- one can choose not to will himself free. In laziness, heedlessness, capriciousness, cowardice, impatience, one contests the meaning of the project at the very moment that one defines it. (Location 247)

- The goal toward which I surpass myself must appear to me as a point of departure toward a new act of surpassing. Thus, a creative freedom develops happily without ever congealing into unjustified facticity. (Location 270)

- There are people who are filled with such horror at the idea of a defeat that they keep themselves from ever doing anything. But no one would dream of considering this gloomy passivity as the triumph of freedom. (Location 288)

- such salvation is only possible if, despite obstacles and failures, a man preserves the disposal of his future, if the situation opens up more possibilities to him. (Location 302)

- just as life is identified with the will-to-live, freedom always appears as a movement of liberation. It is only by prolonging itself through the freedom of others that it manages to surpass death itself and to realize itself as an indefinite unity. (Location 323)

- Existentialism alone gives — like religions — a real role to evil, and it is this, perhaps, which make its judgments so gloomy. Men do not like to feel themselves in danger. Yet, it is because there are real dangers, real failures and real earthly damnation that words like victory, wisdom, or joy have meaning. Nothing is decided in advance, and it is because man has something to lose and because he can lose that he can also win. (Location 344)

Part 2 - Personal Freedom and Others

In Part Two, “Personal Freedom and Others,” de Beauvoir provides a detailed picture of the ways people morally err, especially when they refuse to honor the freedom of others. She starts with an image of childhood, in which the child sees the grown-up world as full of fixed and serious values, but also sees themselves as safely confined to a separate world of play, in which their actions have no moral consequences. As people grow into adolescents, however, they realize that adults are imperfect, values are not absolute, and their own actions have moral and practical consequences. In other words, adolescents realize their freedom, but also their responsibility, and from this point onwards, they have to choose what to do with them—whether to turn their natural freedom into moral freedom or somehow evade the question.

The worst response to this dilemma, according to de Beauvoir, is to become a “sub-man.” The “sub-man” is so afraid of action and its consequences that he tries to do nothing at all—he wishes he were an inanimate object so he would not have to take responsibility for his actions. He sticks to pure objectivity, takes no part in human existence, has no goals nor projects, or a passion for something. He denies his being and his freedom.

The serious man, like the sub-man, tries as hard as possible to deny his own freedom; he does so by choosing and loyally adhering to a set of fixed values that come from somewhere else. He “believes for belief’s sake,” just so that he does not have to confront the responsibility of choosing beliefs based on his own independent thought. lost in the finite

This man supposably becomes pure subjectivity, although in the eyes of the goal, he is a pure object. He loses himself in the pursuit of the external value, and nothing is more important. Whether it is professional, religious, even being a parent or an army man, his existence is completely submerged within it, and only through the eyes of the goal he sees the world. That means that he replaced the ambiguity of freedom, with anxiety and anger, since all who are not part of his goal are his enemies, and he fears events that can hurt his goal.

Next is the nihilist, who accepts the fact that there are no absolute moral values in the world but sees this as a tragedy rather than as an opportunity to seize his freedom and make his own values; the nihilist pursues a will to destruction, “committing disorder and anarchy” in a vain attempt to show everyone else that their values are made up. Often, the nihilist ends up committing suicide—he understands the ambiguity of human life but not his freedom to live anyway. Nihilism

Usually one becomes a nihilist after being a serious man. After giving your all to a cause, only to be disappointed by it, or perhaps by the negative emotions it triggered. From this pain, detachment is brought, and while the person recognizes his freedom, he decides to not use it. He accepts the suffix, that a being is a lack, but rather use is as a positive measure, to fuel yourself to create meaning, goals and projects in the world, it defines the lack as the only aspect of being, he does nothing, believe in nothing.

The next kind of person is the adventurer, who is “close to a genuinely moral attitude” because he eagerly throws himself into a variety of projects and embraces his own freedom. However, the adventurer has no genuine moral commitments; he only wants to conquer and succeed in his projects but does not care what the projects actually are. He is often willing to trample on others’ freedom for the sake of his own enjoyment, and in doing so he proves that he can never be genuinely free because any individual’s genuine freedom relies on the freedom of everyone else (both because of people’s shared humanity and because of people’s concrete interdependence on one another in order to survive in the world). He realizes his being, while denying or ignoring the being of others, treating them as objects, as tools to be used for his own goals.

De Beauvoir’s final figure is the passionate person, who is the inverse of the adventurer and also close to, but just short of, genuine freedom: the passionate person has the right kind of sincere moral commitment, but cares so strongly that he is incapable of detaching himself when he cannot achieve his goals and thus sacrifices his own freedom. Additionally, this person sees others as objects as well.

We see therefore that true moral freedom must extend to the freedom of others. It is not only due to the fact that the infinite value of freedom can only be fulfilled through extension of others freedom (since the individual is destined to die), but also due to the fact that each goal, project, will and value in the world emanates from others. We are standing on the shoulders of those who came before us, on the world that they have built, we have been shaped by our environment, and feel that values are interconnected to others, and are shaped by our interactions with them. All we know, believe, ideas that we hold valuable are possible only due to others and our connection with them Interpersonal Identity. Therefore there is no meaning in existence of an individual, only humanity as a whole.

- child’s situation is characterized by his finding himself cast into a universe which he has not helped to establish, which has been fashioned without him, and which appears to him as an absolute to which he can only submit. In his eyes, human inventions, words, customs, and values are given facts, (Location 356)

- There are beings whose life slips by in an infantile world because, having been kept in a state of servitude and ignorance, they have no means of breaking the ceiling which is stretched over their heads. Like the child, they can exercise their freedom, but only within this universe which has been set up before them, without them. (Location 378)

- it is very rare for the infantile world to maintain itself beyond adolescence. From childhood on, flaws begin to be revealed in it. (Location 398)

- it is not without great confusion that the adolescent finds himself cast into a world which is no longer ready-made, which has to be made; he is abandoned, unjustified, the prey of a freedom that is no longer chained up by anything. (Location 408)

- The child does not contain the man he will become. Yet, it is always on the basis of what he has been that a man decides upon what he wants to be. He draws the motivations of his moral attitude from within the character which he has given himself and from within the universe which is its correlative. (Location 416)

- To exist is to make oneself a lack of being; it is to cast oneself into the world. Those who occupy themselves in restraining this original movement can be considered as sub-men. They have eyes and ears, but from their childhood on they make themselves blind and deaf, without love and without desire. (Location 440)

- The sub-man rejects this “passion” which is his human condition, the laceration and the failure of that drive toward being which always misses its goal, but which thereby is the very existence which he rejects. (Location 443)

- Ethics is the triumph of freedom over facticity, and the sub-man feels only the facticity of his existence. (Location 467)

- The sub-man makes his way across a world deprived of meaning toward a death which merely confirms his long negation of himself. The only thing revealed in this experience is the absurd facticity of an existence which remains forever unjustified if it has not known how to justify itself. (Location 469)

- his freedom in the content which the latter accepts from society. He loses himself in the object in order to annihilate his subjectivity. (Location 480)

- The thing that matters to the serious man is not so much the nature of the object which he prefers to himself, but rather the fact of being able to lose himself in it. (Location 497)

- to believe for belief’s sake, to will for will’s sake is, detaching transcendence from its end, to realize one’s freedom in its empty and absurd form of freedom of indifference. (Location 499)

- As soon as the Idol is no longer concerned, the serious man slips into the attitude of the sub-man. (Location 536)

- He escapes the anguish of freedom only to fall into a state of preoccupation, of worry. Everything is a threat to him, since the thing which he has set up as an idol is an externality and is thus in relationship with the whole universe and consequently threatened by the whole universe; and since, despite all precautions, he will never be the master of this exterior world to which he has consented to submit, he will be constantly upset by the uncontrollable course of events. (Location 548)

- This failure of the serious sometimes brings about a radical disorder. Conscious of being unable to be anything, man then decides to be nothing. We shall call this attitude nihilistic. The nihilist is close to the spirit of seriousness, for instead of realizing his negativity as a living movement, he conceives his annihilation in a substantial way. He wants to be nothing, (Location 558)

- The nihilist attitude manifests a certain truth. In this attitude one experiences the ambiguity of the human condition. But the mistake is that it defines man not as the positive existence of a lack, but as a lack at the heart of existence, (Location 612)

- The adventurer does not propose to be; he deliberately makes himself a lack of being; he aims expressly at existence; though engaged in his undertaking, he is at the same time detached from the goal. (Location 635)

- The man we call an adventurer, on the contrary, is one who remains indifferent to the content, that is, to the human meaning of his action, who thinks he can assert his own existence without taking into account that of others. (Location 660)

- the adventurer devises a sort of moral behavior because he assumes his subjectivity positively. But if he dishonestly refuses to recognize that this subjectivity necessarily transcends itself toward others, he will enclose himself in a false independence which will indeed be servitude. To the free man he will be only a chance ally in whom one can have no confidence; he will easily become an enemy. His fault is believing that one can do something for oneself without others and even against them. (Location 687)

- An end is valid only by a return to the freedom which established it and which willed itself through this end. But this will implies that freedom is not to be engulfed in any goal; neither is it to dissipate itself vainly without aiming at a goal. (Location 763)

- One can reveal the world only on a basis revealed by other men. No project can be defined except by its interference with other projects. To make being “be” is to communicate with others by means of being. (Location 778)

- Only the freedom of others keeps each one of us from hardening in the absurdity of facticity. (Location 783)

Part 3 - Freedom of Communities

In the book’s third and longest part, which is subdivided into five shorter sections, de Beauvoir takes up a series of issues that all center on the relationship between a free individual and the rest of humanity. She has already argued that each person’s freedom depends on everyone else’s, but here she explores the implications of that argument. In the first subsection she argues that “The Aesthetic Attitude,” or the abstracted, distant perspective often taken by critics and philosophers, is intellectuals’ way of evading their own status as concrete, individual, free human beings. In the second subsection, she looks at "Freedom and Liberation," and specifically what the continuous, incremental fight for the freedom of the oppressed looks like from an existentialist perspective. Many are in positions so dire that the only way they can promote their freedom is by a purely negative revolt against the forces that are oppressing them. Oppressors often fear and criminalize this kind of response, but there is no question that the freedom of the oppressed to pursue their goals without being coerced into a way of life they have not chosen is a meaningful freedom, while the oppressor’s freedom to deny others their freedom is no freedom at all (because it undermines others’ freedom, and anyone’s genuine freedom depends on everyone else’s). Oppressors often try to distract people from the value of freedom by creating and elevating other values, like a culture’s distinctive past or the productive potential of capitalism. But tradition and capitalism only matter insofar as they promote freedom, which again proves that freedom is the most fundamental end of human action.

In the third section of her final part, de Beauvoir asks how the oppressed should act for the sake of their freedom. She concludes that it is sometimes necessary to perpetuate injustice in order to fight injustice. This includes committing violence against people who have contributed to oppression out of obligation or ignorance (those who are responsible but not guilty for ignorance), or having to choose one liberation struggle instead of another when two conflict; it can even mean sacrificing one’s comrades or oneself. In order to successfully revolt against tyrants who deny people’s freedom and reduce them to their facticity, people have to use those same tools and reduce both their enemies and themselves to facticity. Both tyrants and revolutionaries promise their followers that their sacrifices are for the sake of a better, freer future, but this is the same mistake that philosophers make when they see ethics as an absolute rather than a respect for freedom embedded in every action. By reducing the individual’s value to zero, tyrants and revolutionaries undermine their own project, turning society’s value to zero, too (since the sum of zero is zero). Tyrants and revolutionaries have to turn their enemies, and also their followers to pure facticity, to objects and tools to be used for their grand goal. This is why de Beauvoir favors democracy, which prioritizes “the dignity of each man” and refuses to sacrifice any for an imagined future fulfillment that will never truly come about (since people’s struggle for freedom has no end). The real ethical problem, however, comes up when one must choose between two people’s competing freedoms; one must decide based on which in turn opens more freedom in the future, which is the same reason that unjust revolution is better than unjust tyranny.

Now that she has shown that the question of whose freedom to prioritize relies on thinking about the future, de Beauvoir turns in the fourth section to the concept of the future, which she argues is split: people both imagine the future as a continuation of the present and hope for a utopian, perfect future, one with no connection to the present, in which “Glory, Happiness, or Justice” magically descends upon the earth. This latter concept of the future is precisely what can convince people to sacrifice the present, but it is based on a false hope for perfection, when in reality all human striving is limited, and ambiguity is a constant feature of existence. Politicians take advantage of people’s wishful thinking and weakness for ideals, promising them a perfect future in order to turn them into instruments; this is how Europe justified colonialism, for instance. Instead, de Beauvoir insists, people should celebrate their existence, their finite projects and finite wills, rather than letting themselves be seduced by the promise of infinity.

In the last section, de Beauvoir returns to the question of ambiguity and investigates in further depth what ethical decision-making requires. She determines that such decisions must aim at the freedom of “the individual as such” and accept violence only when it “opens concrete possibilities to the freedom which I am trying to save.” She offers French politics as an example: the people who consider themselves “enlightened elites” pretend to govern on behalf of France’s colonial subjects, but actually use their gestures to the colonized people’s well-being as a front to continue oppressing and exploiting them. Instead of trying to “civilize” non-Europeans, she thinks, the only ethical stance is to act for the sake of people’s freedom itself. She then looks at the Soviet Union, which has too easily used the goals of its revolution as an excuse to oppress people, even though it is theoretically possible that oppression would sometimes be ethical in order to help push forward people’s liberation. Pursuing this difficult decision—to use violence and oppression to fight violence and oppression—means taking on an enormous responsibility and being extremely vigilant, detailed, and reflective. Needless to say, most politicians and revolutionaries fall short of this standard, which is why they, too, need critics: insofar as they respect freedom, they must embrace free resistance to their own ways.

In a brief conclusion, de Beauvoir offers some big-picture remarks about existentialist ethics’ relationship to her critics and other ethical systems. While existentialism focuses on the individual, since it is the individual who makes free decisions and pursues their own projects, she insists that existentialism is not solipsistic because it sees other people’s freedom as necessary for any individual’s. She asks whether the existentialist conception of subjective moral value is really meaningful, but reminds the reader that nothing is meaningful outside of subjective human perspectives, and that it simply does not make sense to hold human morality to the standard of objective truth, which no individual human could ever access. By centering morality on concrete action and people’s finite projects, de Beauvoir concludes, existentialists affirm individuals’ potential to make concrete contributions to the world and embrace their own freedom; if everyone did this, people could finally stop dreaming about a completely free utopia, because they would have it.

-

2. FREEDOM AND LIBERATION

- Only man can be an enemy for man; only he can rob him of the meaning of his acts and his life because it also belongs only to him alone to confirm it in its existence, to recognize it in actual fact as a freedom. (Location 894)

-

4. THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE

- a democracy which defends itself only by acts of oppression equivalent to those of authoritarian regimes, is precisely denying all these values; whatever the virtues of a civilization may be, it immediately belies them if it buys them by means of injustice and tyranny. (Location 1391)

-

5. AMBIGUITY

- The notion of ambiguity must not be confused with that of absurdity. To declare that existence is absurd is to deny that it can ever be given a meaning; to say that it is ambiguous is to assert that its meaning is never fixed, that it must be constantly won. (Location 1438)

- freedom is achieved absolutely in the very fact of aiming at itself. This requires that each action be considered as a finished form whose different moments, instead of fleeing toward the future in order to find there their justification, (Location 1461)

- In setting up its ends, freedom must put them in parentheses, confront them at each moment with that absolute end which it itself constitutes, and contest, in its own name, the means it uses to win itself. (Location 1496)

- in the case where the content of the action falsifies its meaning, one must modify not the meaning, which is here willed absolutely, but the content itself; however, it is impossible to determine this relationship between meaning and content abstractly and universally: there must be a trial and decision in each case. (Location 1503)

- To want to prohibit a man from error is to forbid him to fulfill his own existence, it is to deprive him of life. (Location 1543)

- the good of an individual or a group of individuals requires that it be taken as an absolute end of our action; but we are not authorized to decide upon this end a priori. The fact is that no behavior is ever authorized to begin with, and one of the concrete consequences of existentialist ethics is the rejection of all the previous justifications which might be drawn from the civilization, the age, and the culture; it is the rejection of every principle of authority. (Location 1593)

-

CONCLUSION

- Man is free; but he finds his law in his very freedom. (Location 1759)

- existentialism does not offer to the reader the consolations of an abstract evasion: existentialism proposes no evasion. On the contrary, its ethics is experienced in the truth of life, and it then appears as the only proposition of salvation which one can address to men. (Location 1786)