Algorithms to Live By

✒️ Note-Making

🔗Connect

🔼Topic:: Decision Making (MOC)

💡Clarify

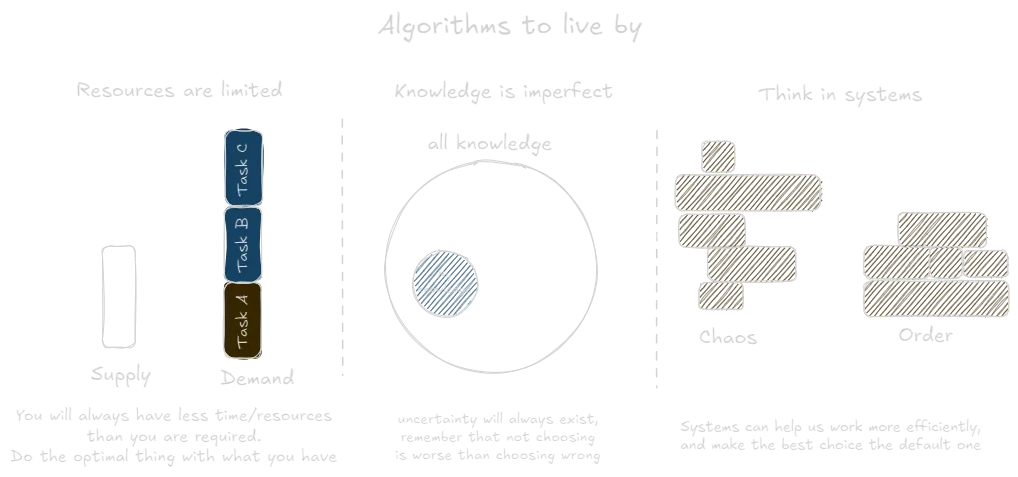

🔈 Summary of main ideas

- Computers and humans are similar

- Take the leap - Sometimes you will need to make a decision before you have complete knowledge, like choosing a candidate before you saw them all. An analysis paralysis would usually lead to the worst outcome because you will miss good opportunities, and pay for not making a decision. That's why it's important to make any decision, given a reasonable base of information.

- Explore while you are young - It is best to explore new options the more you have time/opportunity to benefit from them. Otherwise, we would never know how much better life can be, and we would lose many potential opportunities for improved wellbeing, like trying new types of music. When time is short, stick to the tried and true

- Invest where it matters - Creating a organized system takes time, but it is worth while only if it's important to you, and the alternative (using existing systems/free form) is much worse. Avoid perfectionism, yet focus on efficiency.

- Cache your environment - analyze what's most useful/frequently used, and build your environment in such a way that these things are closest, easily accessible, and with low friction of using.

- Prioritize - You can always focus on do only one thing at a time. Therefore, you should have a clear list of what comes first.

- Solve the easier task - When something seems impossible, ask yourself "what if it was easy". Imagine a simpler situation, and the solution to that one might be the best solution that can be found for the hard case as well

- Give many, yet not equal chances - Your trust is not an either/or, people should have a way to earn back your trust, but the more they let you down, the harder they have to work to get it back.

- Build systems for cooperation - Sometimes the status quo is not the best possible solution. In order to switch to a better one, we need to design systems that will guide us (like bowling lanes) towards the optimal solution, limiting, punishing and encouraging when necessary.

🗒️Relate

⛓ by following this method, what will happen? What is the goal of this book?

🔍Critique

✅ relevant research, metaphors or examples that helps to convey the argument

❌ the logical jumps, holes or simply cases where it is wrong... many of the situations computer face are in controlled settings, where there are limitations on inputs or outputs, such that the computer could understand and find the optimal solution. in human life, things are much more vague, abstract and undefined, so not all algorithms will be easy to implement or even give guidelines to how to start solving a problem.

🧱 Implementations and limitations of it are...

🗨️Review

💭 my opinions on the book, the writers style... many of these algorithms are the results of carful and creative thinking in an experiment like environment which simulates human decision making, or at least the rational side that wants optimal outcomes in least resources spent. many cases in our day to day life could be improved by implementing them.

🖼️Outline

📒 Notes

Intro

- “optimal stopping” problems. The 37% rule defines a simple series of steps—what computer scientists call an “algorithm”—for solving these problems.

- algorithm is just a finite sequence of steps used to solve a problem, and algorithms are much broader—and older by far—than the computer. Long before algorithms were ever used by machines, they were used by people.

- Optimal stopping tells us when to look and when to leap. The explore/exploit tradeoff tells us how to find the balance between trying new things and enjoying our favorites. Sorting theory tells us how (and whether) to arrange our offices. Caching theory tells us how to fill our closets. Scheduling theory tells us how to fill our time.

- tackling real-world tasks requires being comfortable with chance, trading off time with accuracy, and using approximations.

- Thinking algorithmically about the world, learning about the fundamental structures of the problems we face and about the properties of their solutions, can help us see how good we actually are, and better understand the errors that we make.

Optimal Shopping Problem

The optimal shopping problem is a set of cases where you are presented a series of "products", one each time, and have to decide whether to take the one's in front of you or look at the next option, not knowing what is the quality of the next one. But once you passed, you cant choose it anymore, its gone. A common example is hiring a worker, you sit at the interview and you can judge the quality of the interviewee, and you can decide whether to hire him or not, but once you skip he might be out of the market by the next time you decide to approach him. So how would you know if you hired the best worker, or whether you should wait longer? The answer lies in the look and leap algorithm Leap Into Faith. Mathematically, after seeing 37% of the market (for example, the pool of workers), then you should take the one that its better than any that you have seen before. Meaning you don't take anyone of the first 37% of the pool. This algorithm would give you about 37% of choosing the best candidate, and it improves the larger the pool is. This is the optimal balance point between taking the first candidate (stopping too early) and taking the last one (stopping too late). We should estimate based on what we've seen so far the value of the candidate and the expected value of candidates to come. The trick is remembering that you don't only have to find a good evaluation method for the quality of the candidate, but also a way to guess the size of the pool. In relationships, this will be equivalent to finding a partner at age 26-28, if you started looking for one in age 18, and you want to settle down by 40. When to Quit

This was true for cases where candidates are evaluated ordinally, which means there's no absolute measure of value, but you can rank the candidates by which is better. However, if there's a cardinal score, like an IQ test, you can raise the threshold. The danger here of course is treating these numeric measures as the only proxy for value, thus missing qualitative aspects that are hard to measure or compare cardinally. McNamara Fallacy

These examples - when to choose a worker/partner, when to quit or sell a house, have an important common trait. This is the cost of not making a decision, for example the cost in terms of productivity but not hiring a worker yet, or sadness of being alone. Its hard to model these costs.

An important factor in making rational decisions is not only to endlessly analyze and compare the choices, but also knowing when to stop. Analysis paralysis

- In any optimal stopping problem, the crucial dilemma is not which option to pick, but how many options to even consider.

- Look-Then-Leap Rule: You set a predetermined amount of time for “looking”—that is, exploring your options, gathering data—in which you categorically don’t choose anyone, no matter how impressive. After that point, you enter the “leap” phase, prepared to instantly commit to anyone who outshines the best applicant you saw in the look phase.

- 37% Rule: look at the first 37% of the applicants,* choosing none, then be ready to leap for anyone better than all those you’ve seen so far.

- in the face of slim pickings, lower your standards. It also makes clear the converse: with more fish in the sea, raise them. In both cases, crucially, the math tells you exactly by how much.

- Any yardstick that provides full information on where an applicant stands relative to the population at large will change the solution from the Look-Then-Leap Rule to the Threshold Rule and will dramatically boost your chances of finding the single best applicant in the group.

- our threshold depends only on the cost of search. Since the chances of the next offer being a good one—and the cost of finding out—never change, our stopping price has no reason to ever get lower as the search goes on, regardless of our luck. We set it once, before we even begin, and then we quite simply hold fast.

- Intuitively, we think that rational decision-making means exhaustively enumerating our options, weighing each one carefully, and then selecting the best. But in practice, when the clock—or the ticker—is ticking, few aspects of decision-making (or of thinking more generally) are as important as one: when to stop.

Explore/Exploit

we all have the dilemma between sticking to the "tried and true" (exploit) and trying something new, in hopes that it will be better than what we know (explore). exploration vs exploitation. for example - new music, restaurants, people, etc. the dilemma is affected by three attributes:

- Time - how long do we have to enjoy those things? The value of new things (that might be better than the existing), depends on how long do we have to enjoy the switch. For example if I went on a vacation, its better to stick to popular restaurants than take a gamble on the last day since it might be a bad restaurant, but if I moved to a new location, its better to explore which good restaurants are there. For example, age is an important factor in humans. Babies tend to explore more, compare to elderly that tend to exploit. Since as a kid you have little to gain from exploit (you still dont know anything) and a lot to gain by exploring (since the time horizon is very large), and vice versa for elderly.

- Future value - the more I appreciate future enjoyment more, the lower the cost of explore is. If fun tomorrow is equal to 50% of fun today, then I have a discount rate of about a 50%. Since exploring is paying a cost now (uncertainty + switching costs) to have more fun in the future. Present Bias

- Chances of finding something better - we don't know what are the chances that there is a better restaurant out there (similar to the optimal shopping problem). The higher the risk, the higher the exploration cost. Usually its information we only have during exploration.

- Regret - which strategy will cause us the least Regret (on the choices we didn't make). we can stick to a strategy that will minimize regret, which means making most of the mistakes at the beginning, so that we will learn and improve and have less regret as we continue making choices (interesting to compare with the common definition of regret, which usually comes at the end of the road, where there's no more flexibility to change and the amount of error is discovered). The way to minimize regret is based on the expected range of our utility. its bigger (worse) the more uncertainty there is. The "upper confidence bound" is a strategy that potentially can give the best result giving the information that we have now. practically it means be optimistic as possible, assume the best on people, places, choices, this will minimize regret.

- Remembering that every “best” song and restaurant among your favorites began humbly as something merely “new” to you is a reminder that there may be yet-unknown bests still out there—and thus that the new is indeed worthy of at least some of our attention.

- exploration is gathering information, and exploitation is using the information you have to get a known good result.

- People tend to treat decisions in isolation, to focus on finding each time the outcome with the highest expected value. But decisions are almost never isolated, and expected value isn’t the end of the story. If you’re thinking not just about the next decision, but about all the decisions you are going to make about the same options in the future, the explore/exploit tradeoff is crucial to the process.

- When balancing favorite experiences and new ones, nothing matters as much as the interval over which we plan to enjoy them.

- A sobering property of trying new things is that the value of exploration, of finding a new favorite, can only go down over time, as the remaining opportunities to savor it dwindle.

- With the future weighted nearly as heavily as the present, the value of making a chance discovery, relative to taking a sure thing, goes up even more.

- Exploration in itself has value, since trying new things increases our chances of finding the best. So taking the future into account, rather than focusing just on the present, drives us toward novelty.

- First, assuming you’re not omniscient, your total amount of regret will probably never stop increasing, even if you pick the best possible strategy—because even the best strategy isn’t perfect every time. Second, regret will increase at a slower rate if you pick the best strategy than if you pick others; what’s more, with a good strategy regret’s rate of growth will go down over time, as you learn more about the problem and are able to make better choices.

- an Upper Confidence Bound algorithm doesn’t care which arm has performed best so far; instead, it chooses the arm that could reasonably perform best in the future.

- Following the advice of these algorithms, you should be excited to meet new people and try new things—to assume the best about them, in the absence of evidence to the contrary. In the long run, optimism is the best prevention for regret.

- Within a decade or so after its first tentative use, A/B testing was no longer a secret weapon. It has become such a deeply embedded part of how business and politics are conducted online as to be effectively taken for granted.

- In general, it seems that people tend to over-explore—to favor the new disproportionately over the best.

- To live in a restless world requires a certain restlessness in oneself. So long as things continue to change, you must never fully cease exploring.

- Childhood gives you a period in which you can just explore possibilities, and you don’t have to worry about payoffs because payoffs are being taken care of by the mamas and the papas

- as people approach the end of their lives, they want to focus more on the connections that are the most meaningful.

- life should get better over time. What an explorer trades off for knowledge is pleasure.

Sort / Search

Indexing is an action that takes a long time, and usually grows in a faster (non linear way) the larger the data size is (more things to index). There is a trade off between sorting and search, which is time. Sorting takes time to make, but makes searches faster, so the question is whether sorting is worth it in each case. Multiplier For example mails are not worth to sort because usually our email search engine is good as it is.

There are several sorting methods:

- Bubble sort - the worst option! each time we compare two objects and we push them down / up one space depending on who's first (which means to compare each two possible combinations of row in the data)

- Insert sort - we empty the list and bring back one item at a time, and each new item is compared to the items in the existing list

- Mega sort - the most efficient. the list is divided into pairs which are sorted (because its the most easy to compare only 2 items). then you compare each mini-list with another list and merge them (using an insert sort), until finally you merge all the lists together into a single, sorted list.

- Bucket sort - when you dont care about the sort between individual rows, only the category they fall into. its faster but less accurate.

sorting in real life is like a competition, and the way you construct the competition is the sorting method, and it will affect the final order of the winners. The best and fastest way would be to compare all competitors to an external measurement, like a race that you get the exact cardinal order of winners without dispute (he who ran fastest is first, second is second...). That way you don't have to compare each pair separately but all at once.

In a sense, sorting is a form of Upfront costs, which might worth the investment if the difference between sorted and unsorted is large. Try to avoid the trap of Perfectionism, don't sort for the sake of sorting, this is just a waste of resources.

- sorting is essential to working with almost any kind of information. Whether it’s finding the largest or the smallest, the most common or the rarest, tallying, indexing, flagging duplicates, or just plain looking for the thing you want, they all generally begin under the hood with a sort.

- This is the first and most fundamental insight of sorting theory. Scale hurts.

- Sorting something that you will never search is a complete waste; searching something you never sorted is merely inefficient.

- The search-sort tradeoff suggests that it’s often more efficient to leave a mess.

- two separate downsides to the desire of any group to sort itself. You have, at minimum, a linearithmic number of confrontations, making everyone’s life more combative as the group grows—and you also oblige every competitor to keep track of the ever-shifting status of everyone else, otherwise they’ll find themselves fighting battles they didn’t need to.

- Having a benchmark—any benchmark—solves the computational problem of scaling up a sort.

Memory (cache)

Memory is convenient since it makes extraction easier, like keeping a useful book nearby instead of taking it from the library each time you want to read. The question is, given limited memory space, what do we keep and what do we throw away. Preferably we will keep what's most likely that we will use again, but we cant always know that in advance. The second best solution is the last recently used, meaning the item we last used is the most likely to be used again.

Caching has physical significance as well. physical distance affects extraction speed. For example libraries put the most recent lent books in the front. Amazon has local warehouses with the most likely to be ordered items from that region, Netflix has a similar concept with their servers. In your personal life:

- Store by use, not category - For example, have one drawer for the most useful things, no matter which category they belong to.

- Caching levels - The most precious one for example, a drawer next to the desk, a second one - a closest, third level - a warehouse. Each level is a tradeoff between speed and space. (drawer is smaller but closest, while a warehouse is large but far).

- Proximity is key - Keep things next to where they will be used. keep your gym cloths next to the door, or your notebooks next to your desk. Friction

since the cost of searching and caching is depended on the size of the memory, we can say that aging memory problem is not a problem of forgetting our memories, but simply a higher cost of retrieving them because of higher caching costs. Caching

- Unless we have good reason to think otherwise, it seems that our best guide to the future is a mirror image of the past. The nearest thing to clairvoyance is to assume that history repeats itself—backward.

- This fundamental insight—that in-demand files should be stored near the location where they are used—also translates into purely physical environments.

- Having a cache is efficient, but having multiple levels of caches—from smallest and fastest to largest and slowest—can be even better. Where your belongings are concerned, your closet is one cache level, your basement another, and a self-storage locker a third.

- if you follow the LRU principle—where you simply always put an item back at the very front of the list—then the total amount of time you spend searching will never be more than twice as long as if you’d known the future. That’s not a guarantee any other algorithm can make.

- If the pattern by which things fade from our minds is the very pattern by which things fade from use around us, then there may be a very good explanation indeed for the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve—namely, that it’s a perfect tuning of the brain to the world, making available precisely the things most likely to be needed.

- the fundamental challenge of memory really is one of organization rather than storage,

- older brains—which must manage a greater store of memories—are literally solving harder computational problems with every passing day.

Scheduling

how computers priorities tasks

- we encounter the first lesson in single-machine scheduling literally before we even begin: make your goals explicit. We can’t declare some schedule a winner until we know how we’re keeping score.

- If you’re concerned with minimizing maximum lateness, then the best strategy is to start with the task due soonest and work your way toward the task due last. This strategy, known as Earliest Due Date,

- Minimizing the sum of completion times leads to a very simple optimal algorithm called Shortest Processing Time: always do the quickest task you can.

- In scheduling, this difference of importance is captured in a variable known as weight. When you’re going through your to-do list, this weight might feel literal—the burden you get off your shoulders by finishing each task. A task’s completion time shows how long you carry that burden, so minimizing the sum of weighted completion times (that is, each task’s duration multiplied by its weight) means minimizing your total oppression as you work through your entire agenda.

- Computer science can offer us optimal algorithms for various metrics available in single-machine scheduling, but choosing the metric we want to follow is up to us. In many cases, we get to decide what problem we want to be solving.

- a love of getting things done isn’t enough to avoid scheduling pitfalls, and neither is a love of getting important things done. A commitment to fastidiously doing the most important thing you can, if pursued in a head-down, myopic fashion, can lead to what looks for all the world like procrastination.

- the weighted version of Shortest Processing Time is a pretty good candidate for best general-purpose scheduling strategy in the face of uncertainty. It offers a simple prescription for time management: each time a new piece of work comes in, divide its importance by the amount of time it will take to complete. If that figure is higher than for the task you’re currently doing, switch to the new one; otherwise stick with the current task.

- When the future is foggy, it turns out you don’t need a calendar—just a to-do list.

- the machine that is doing the scheduling and the machine being scheduled are one and the same. Which makes straightening out your to-do list an item on your to-do list—needing, itself, to get prioritized and scheduled. Second, preemption isn’t free. Every time you switch tasks, you pay a price, known in computer science as a context switch.

- Computers multitask through a process called “threading,” which you can think of as being like juggling a set of balls. Just as a juggler only hurls one ball at a time into the air but keeps three aloft, a CPU only works on one program at a time, but by swapping between them quickly enough (on the scale of ten-thousandths of a second) it appears to be playing a movie, navigating the web, and alerting you to incoming email all at once.

- Thrashing is a very recognizable human state. If you’ve ever had a moment where you wanted to stop doing everything just to have the chance to write down everything you were supposed to be doing, but couldn’t spare the time, you’ve thrashed. And the cause is much the same for people as for computers: each task is a draw on our limited cognitive resources. When merely remembering everything we need to be doing occupies our full attention—or prioritizing every task consumes all the time we had to do them

- the best strategy for getting things done might be, paradoxically, to slow down.

- you should try to stay on a single task as long as possible without decreasing your responsiveness below the minimum acceptable limit.

Bayes Rule

- This is the crux of Bayes’s argument. Reasoning forward from hypothetical pasts lays the foundation for us to then work backward to the most probable one.

- Bayes’s Rule. And it gives a remarkably straightforward solution to the problem of how to combine preexisting beliefs with observed evidence: multiply their probabilities together.

- These three very different patterns of optimal prediction—the Multiplicative, Average, and Additive Rules—all result directly from applying Bayes’s Rule to the power-law, normal, and Erlang distributions, respectively.

- the ability to resist temptation may be, at least in part, a matter of expectations rather than willpower.

Overfitting

- The question of how hard to think, and how many factors to consider, is at the heart of a knotty problem that statisticians and machine-learning researchers call “overfitting.” And dealing with that problem reveals that there’s a wisdom to deliberately thinking less.

- it is indeed true that including more factors in a model will always, by definition, make it a better fit for the data we have already. But a better fit for the available data does not necessarily mean a better prediction.

- overfitting poses a danger any time we’re dealing with noise or mismeasurement—and we almost always are.

- it’s incredibly difficult to come up with incentives or measurements that do not have some kind of perverse effect.

- we must balance our desire to find a good fit against the complexity of the models we use to do so.

- A bit of conservatism, a certain bias in favor of history, can buffer us against the boom-and-bust cycle of fads. That doesn’t mean we ought to ignore the latest data either, of course. Jump toward the bandwagon, by all means—but not necessarily on it.

- The effectiveness of regularization in all kinds of machine-learning tasks suggests that we can make better decisions by deliberately thinking and doing less.

- The greater the uncertainty, the bigger the gap between what you can measure and what matters, the more you should watch out for overfitting

Relaxation

Solve the easier problem Some optimization problems are too complicated, and the more complicated they are, the harder it is to evaluate and find the optimal solution. for example: what is the shortest route that passes through each city in the world without going back or being in the same city twice.

To facilitate these problems, we can "relax" them, which means reducing the limitations which can bring to a near-optimal solution that otherwise wouldn't have been found. methods for relaxion:

- remove limitations (you can visits the same visit twice)

- due partial estimations (instead of 100% of visiting each city, every city has 50% chance of being visited)

- Stretch the limits (the results can go over the allowed deadline by a margin)

- Constraint Relaxation: to make the intractable tractable, to make progress in an idealized world that can be ported back to the real one. If you can’t solve the problem in front of you, solve an easier version of it—and then see if that solution offers you a starting point, or a beacon, in the full-blown problem. Maybe it does.

- There are many ways to relax a problem, and we’ve seen three of the most important. The first, Constraint Relaxation, simply removes some constraints altogether and makes progress on a looser form of the problem before coming back to reality. The second, Continuous Relaxation, turns discrete or binary choices into continua: when deciding between iced tea and lemonade, first imagine a 50–50 “Arnold Palmer” blend and then round it up or down. The third, Lagrangian Relaxation, turns impossibilities into mere penalties, teaching the art of bending the rules (or breaking them and accepting the consequences).

- Unless we’re willing to spend eons striving for perfection every time we encounter a hitch, hard problems demand that instead of spinning our tires we imagine easier versions and tackle those first. When applied correctly, this is not just wishful thinking, not fantasy or idle daydreaming. It’s one of our best ways of making progress.

Randomness

Randomness allows us to solve complicated problems that we otherwise cant compute. For example we cant have a survey for 100% of the citizens of a state, its too costly. use cases:

- random sampling - each policy would benefit some and hurt others, so by checking a random sample we can see who gets hurt. relying on averages would probably conceal these kinds of negative outcomes

- Finding global optimum - normal computation might get stuck on a local optimum point, but by forcing him to move randomly to a different point, he might be able to find the global optimum.

- sampling is better because it gives you an answer at all, in cases where nothing else will.

- Being randomly jittered, thrown out of the frame and focused on a larger scale, provides a way to leave what might be locally good and get back to the pursuit of what might be globally optimal.

- First, from Hill Climbing: even if you’re in the habit of sometimes acting on bad ideas, you should always act on good ones. Second, from the Metropolis Algorithm: your likelihood of following a bad idea should be inversely proportional to how bad an idea it is. Third, from Simulated Annealing: you should front-load randomness, rapidly cooling out of a totally random state, using ever less and less randomness as time goes on, lingering longest as you approach freezing.

Network (connectiveness)

Communication between computers is like mail - each side sends a package to the other side. that way you can communicate asynchronously, without a constant connection (the difference between whatsapp and a phone call). problems:

- how do you approve you received the package? each side adds a number to the package, and the other side repeats that number. for example, "got number 10", if the first sides keeps on sending new messages, but the other side has not confirm, we know we have to resend or that there's a bigger problem. That means that most of our communication is "meta", the announcement of receiving the messages instead of actually delivering the content of the message.

- What happens when two sources send packages at the same time (like interrupting someone on the phone). We due an exponential backoff, which means - if there was a clash, I shall wait 1 second. if there was another, I will wait 5 seconds, than 1 minute, the 5 minutes... This enables more smooth communication (since you don't spam the network, you wait longer and longer).

every network has two attributes:

- Latency - the speed which the information flows

- Bandwidth - the amount of information that can flow at any given moment When the information flowing into the network is higher than the amount it can process, we are experiencing a delay. At some point, networks will simply ignore any new request since the backlog has reached its maximum.

examples for exponential backoff in real life - instead of giving each person an equal amount of tries and after that there's no going back, we should give them infinite tries but with larger thresholds for success. for example - on your first criminal offense, get only 1 day in jail, the second time, 5 days, etc... Binary Thinking if a friend has let you down, don't burn the bridge. give him another chance but he will have to work harder to prove to you that he's worthy of your Trust. We sometimes forget to have an "ignore threshold" in our personal lives. For example we let social media interrupted us constantly even when we can no longer take it. We should therefore set a threshold, for example - "from six o'clock I don't receive new messages/emails, any new message would be deleted - and not treated on a later date" Boundaries.

- one can imagine a corporation in which, annually, every employee is always either promoted a single step up the org chart or sent part of the way back down.

- The most prevalent critique of modern communications is that we are “always connected.” But the problem isn’t that we’re always connected; we’re not. The problem is that we’re always buffered. The difference is enormous. The feeling that one needs to look at everything on the Internet, or read all possible books, or see all possible shows, is bufferbloat.

- Rather than warning senders of above-average queue times, it might warn them that it was simply rejecting all incoming messages.

Game Theory

Nash equilibrium is not always easy to find, and even if it does exist, its not necessarily good, like the equilibrium in the prisoner's dilemma. One possible answer is to create mechanisms that promote switching to the optimal state, for example forcing cooperation by increasing the penalty for "snitching". Similarly, auctions are planned in a way that will make telling the truth the dominant's strategy. Nudge We can view emotions, especially anger and revenge as social mechanisms that are used to create those balances, and to push us towards "better" or more righteous equilibriums. Emotions as decision heuristics. Individuals are willing to pay a higher personal cost to reduce crimes, and vices and by that they improve the social optimum. Secondly, there are harmful equilibriums that are caused by information gaps, or between "personal" and "public" information. When I deduce wrongful conclusions from someone else's behaviors on his reasons for action we can cause a destructive herd mentality where everyone is supposedly "rational", but the result is catastrophic. Game Theory

- Optimal stopping problems spring from the irreversibility and irrevocability of time; the explore/exploit dilemma, from time’s limited supply. Relaxation and randomization emerge as vital and necessary strategies for dealing with the ineluctable complexity of challenges like trip planning and vaccinations.

- any time a system—be it a machine or a mind—simulates the workings of something as complex as itself, it finds its resources totally maxed out, more or less by definition. Computer scientists have a term for this potentially endless journey into the hall of mirrors, minds simulating minds simulating minds: “recursion.”

- In a game-theory context, knowing that an equilibrium exists doesn’t actually tell us what it is—or how to get there.

- The predictive abilities of Nash equilibria only matter if those equilibria can actually be found by the players.

- A low price of anarchy means the system is, for better or worse, about as good on its own as it would be if it were carefully managed. A high price of anarchy, on the other hand, means that things have the potential to turn out fine if they’re carefully coordinated—but that without some form of intervention, we are courting disaster.

- The very stability that these bad equilibria have, the thing that makes them equilibria, becomes damnable. By and large we cannot shift the dominant strategies from within. But this doesn’t mean that bad equilibria can’t be fixed. It just means that the solution is going to have to come from somewhere else.

- by reducing the number of options that people have, behavioral constraints of the kind imposed by religion don’t just make certain kinds of decisions less computationally challenging—they can also yield better outcomes.

- we might hazard that emotion is mechanism design in the species. Precisely because feelings are involuntary, they enable contracts that need no outside enforcement.

- the rational argument for love is twofold: the emotions of attachment not only spare you from recursively overthinking your partner’s intentions, but by changing the payoffs actually enable a better outcome altogether. What’s more, being able to fall involuntarily in love makes you, in turn, a more attractive partner to have.

- under the right circumstances, a group of agents who are all behaving perfectly rationally and perfectly appropriately can nonetheless fall prey to what is effectively infinite misinformation. This has come to be known as an “information cascade.”

- For one, be wary of cases where public information seems to exceed private information, where you know more about what people are doing than why they’re doing it, where you’re more concerned with your judgments fitting the consensus than fitting the facts. When you’re mostly looking to others to set a course, they may well be looking right back at you to do the same. Second, remember that actions are not beliefs; cascades get caused in part when we misinterpret what others think based on what they do.

- any game that can be played for you by agents to whom you’ll tell the truth, it says, will become an honesty-is-best game if the behavior you want from your agent is incorporated into the rules of the game itself.

- If changing strategies doesn’t help, you can try to change the game. And if that’s not possible, you can at least exercise some control about which games you choose to play. The road to hell is paved with intractable recursions, bad equilibria, and information cascades. Seek out games where honesty is the dominant strategy. Then just be yourself.

Conclusion

- Even the best strategy sometimes yields bad results—which is why computer scientists take care to distinguish between “process” and “outcome.” If you followed the best possible process, then you’ve done all you can, and you shouldn’t blame yourself if things didn’t go your way.

- computation is bad: the underlying directive of any good algorithm is to minimize the labor of thought.

- We can be “computationally kind” to others by framing issues in terms that make the underlying computational problem easier.

- Politely withholding your preferences puts the computational problem of inferring them on the rest of the group. In contrast, politely asserting your preferences (“Personally, I’m inclined toward x. What do you think?”) helps shoulder the cognitive load of moving the group toward resolution.

- One of the chief goals of design ought to be protecting people from unnecessary tension, friction, and mental labor.