We guard our time fiercely, yet one small unexpected event can ruin an entire day. How can we manage our schedules effectively when life consistently refuses to follow the plan?

The Clock is Ticking

"Time is money" - and we treat it as such. We guard our time, track our expenditures, and grow stressed when it runs out.

Because time is less tangible than money, it requires more complex systems to protect. To this end, we use Pomodoro timers for focus and time-blocking for planning. We also automate, delegate, and set countless reminders, checklists, and commitment devices.

We bring order to the chaos of our lives, reduce uncertainty wherever possible, and get annoyed when something does not go "according to plan."

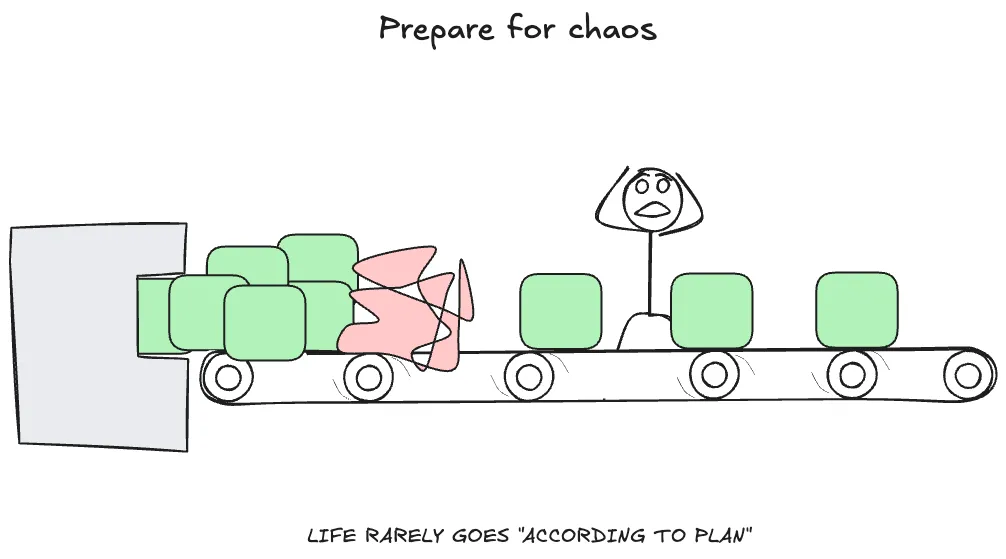

Life becomes like a giant production line-there is beauty in its efficiency, but a single malfunction can quickly escalate into a disaster.

For example, getting stuck in traffic on your commute forces you to leave work later than expected, which then interrupts your evening plans. A delay of a few minutes in the morning has wrecked your entire day.

Our life is not a production line. We cannot control time any more than we can control the movement of the planets. To imagine we can is to set ourselves up for failure and burnout.

We do not own time; it is not ours to begin with. We can only decide what to do with the time that has been given to us.

Our lives are deeply intertwined with things beyond our control-other people, random events, the weather, the economy, and more. It is so hard for us to control ourselves that expecting others to align perfectly with our internal expectations is borderline insanity.

But what is the alternative?

Prepare for Chaos

If we cannot control time, should we give up trying? This approach would leave us like a leaf in the wind, entirely at the mercy of external events. Embracing uncertainty is a deep-seated fear for humans; we crave certainty and control, so how can we give up on them?

As you might have guessed, I am not in favor of losing our agency. Instead, we should change our perspective on what it means to have agency.

On a practical level, this means adopting one or more of the following strategies:

- Plan B - We do not know what might go wrong, but it is likely that something will. Have an alternative in case your main plan fails. For example, if you get delayed at work and do not have time for the gym, do a 10-minute session at home instead. A short and easy alternative provides a sense of progress while still fitting into your interrupted schedule.

- Buffers - If you usually plan to arrive at work by 8:00, do not schedule meetings before 8:30. This margin gives you flexibility when the commute takes longer or something unexpected comes up. Whatever buffer you think is enough, double it-we tend to underestimate delays.

- Fewer dependencies - If you only write on your computer, you are limited to writing at home. Try finding a way to write on your phone as well. Flexible habits are harder to break.

But regardless of how we plan for uncertainty, we must accept that we are fighting forces stronger than us. Sometimes, even our backup plan will fail. Sometimes, we will not have any good choices. Sometimes, we will feel helpless.

Randy Pausch was a successful computer scientist until his doctor informed him that he had terminal cancer with only a few months to live. What he said afterward brought him fame: "We cannot change the cards we are dealt, just how we play the hand."

The Stoic emperor Marcus Aurelius would have agreed, saying, "The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way."

We fall, we get back up, and we repeat. This is both our burden and our strength. Obstacles will keep coming, much like the endless task of pushing a boulder up a hill, but we have the power to overcome.

"The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy," said Albert Camus. If Sisyphus can be happy, why can't we?